Hakka in Taiwan and Worldwide

The Hakka Way: Survival and Evolving Identity

1-30

This month, we invite readers to practice lectio divina—a prayerful reading of Scripture. Together, we will reflect on the work of the Holy Spirit: first reading the passage, then meditating deeply on a single verse, allowing it to shape our hearts and flow naturally into action.

Dandelion Resilience:

The Hakka Philosophy of Life

The Hakka Philosophy of Life

Whether drifting on water, riding the wind, or hitching a ride on an animal’s fur, a dandelion always finds a way to take root in new soil. Its feathery white puff may seem fragile, yet it holds remarkable resilience—just like the Hakka people, whose gentle exterior conceals a steadfast strength.

Throughout history, the Hakka have migrated many times. As “latecomers,” they often found themselves on the social margins. They could not claim the most fertile fields or occupy the centers of wealth and power. Instead, they carved out a place for themselves in the mountains and on barren lands, clearing wilderness to survive. In such harsh conditions, unity was essential.

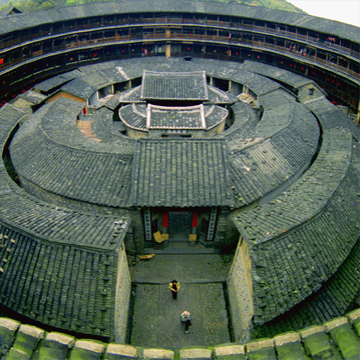

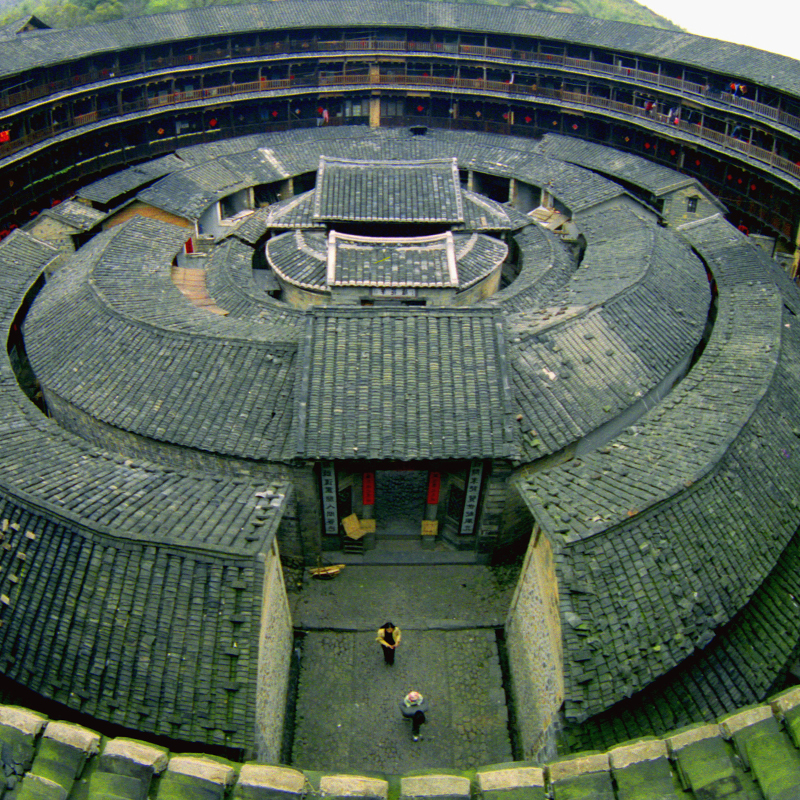

They lived in fortified walled villages—not only to guard against external threats but also to foster mutual support within the clan, sharing resources and standing together against external pressures. They formed tightly woven kinship networks to resist competitors in unfamiliar lands and ensure the survival and continuity of their lineage. Their closed lifestyle, with limited interaction and intermarriage with outsiders, also preserved a thread of Hakka culture through the generations.

The Hakka philosophy of food is one of saltiness, savor, and endurance. In times of scarcity, they learned to stretch the value of a single piece of meat or a single vegetable. The rich, time-mellowed flavors of preserved mustard greens braised with pork carry the wisdom of generations, while the delicate craft of stuffed tofu reveals their deep respect for ingredients and their determination to waste nothing. These humble yet profound flavors reflect the very essence of the Hakka spirit—creating abundance from what is limited, and finding the fullest possibilities within the simplest means.

Like dandelions carried by the wind, the Hakka journeyed wherever the winds of life took them—and yet, wherever they settled, they took root and stood strong. But this was the face of the Hakka people before the dawn of the 21st century.

From Singular to Plural:

The Shifting Identity of the Hakka

The Shifting Identity of the Hakka

In the 21st century, the Hakka are no longer who they once were. In the past, they were known for their courage, frugality, and resilience—often working the land, mining, or building railroads, enduring physically demanding labor. Today, however, the global Hakka community embraces a wide range of professions. Generations of cultural exchange and migration have reshaped their identity, making the old labels that once defined Hakka culture no longer sufficient. In this new era, Hakka identity is more complex, multifaceted, and harder to pin down.

In today’s globalized world, cultural boundaries are increasingly blurred and continually reshaped. Historically, in their ancestral homeland in China, the Hakka remained relatively isolated and conservative, with little contact with other cultural groups. This allowed them to preserve a more traditional and unified sense of Hakka identity. But as they migrated across regions and nations, their encounters and exchanges with local cultures continually reshaped who they were—transforming a once singular identity into a diverse and multifaceted sense of belonging.

Consider a Hakka descendant who grew up in Thailand, holds an Australian passport, married a Canadian, and now lives in Amsterdam. They’re familiar with Thai cuisine, speak Thai, Hakka, and Mandarin, have a Western educational background, and navigate a cross-cultural marriage. When visiting relatives in Thailand, they love reminiscing about childhood memories. When meeting Taiwanese, they naturally switch to Mandarin. When encountering Malaysian Hakka, they speak Hakka. Yet at home, English is the primary language. This fluid switching between languages reflects their layered identities, which shift effortlessly depending on the people they meet and the context they’re in. Still, “being Hakka” remains part of who they are—sometimes highlighted, sometimes tucked away. If you ask, “So, where are you from?” it’s not a question with a simple answer; it’s one that often lingers, inviting reflection.

Is this an identity crisis? Perhaps not. What is certain is that it’s a product of globalization. Across the world, especially among younger generations, most Hakka carry multiple layers of identity, challenging the traditional notion that one can only have a single, fixed sense of belonging. Global Hakka navigate these multiple identities with ease, choosing when to express or downplay their Hakka identity depending on the situation—allowing them to move fluidly between different communities and conversations.

Another effect of globalization is the gradual marginalization of the Hakka language. Factors like intermarriage, national language policies, and smaller family sizes have reduced opportunities for younger generations to learn Hakka. “Can you still be considered Hakka if you don’t speak the language?”—this is a shared question and challenge faced by Hakka communities around the world.

From “Sojourning” to “Coming Home”

In Hakka studies, scholars often examine the global Hakka, Taiwanese Hakka, Chinese Hakka, and Hong Kong Hakka as distinct groups. The global Hakka—shaped by repeated migrations and cross-border movements—carry fluid, multi-layered identities, with their sense of “Hakka-ness” continually being reshaped. In contrast, Taiwanese Hakka went through the Qing era, Japanese colonial rule, and the Kuomintang’s Mandarin-only policies, until the post-martial-law “Return Our Mother Tongue” movement sparked a revival. Today, Taiwan has become one of the strongest centers for preserving Hakka culture. Meanwhile, Chinese and Hong Kong Hakka have each developed their own unique cultural contexts shaped by different historical, political, and economic forces.

Due to space constraints, this month’s Mission Pathway draws on the work of Hakka scholars to help readers better understand the global and Taiwanese Hakka. The Hakka people’s long history of migration—and their very name, meaning “guest families”—reflects a shared state of mind. Whether they are traditional Hakka or a new generation shaped by globalization and multiple identities, deep within remains a longing and search for “home.”

We believe God can move the hearts of Hakka people from every background, and that the gospel—expressed in many forms—can reach Hakka communities around the world. Through it, they may come to a deeper understanding of their true identity: that all humanity are sojourners, longing for an ultimate home. The Holy Spirit will lead the Hakka from living as “guests” to truly “coming home.”

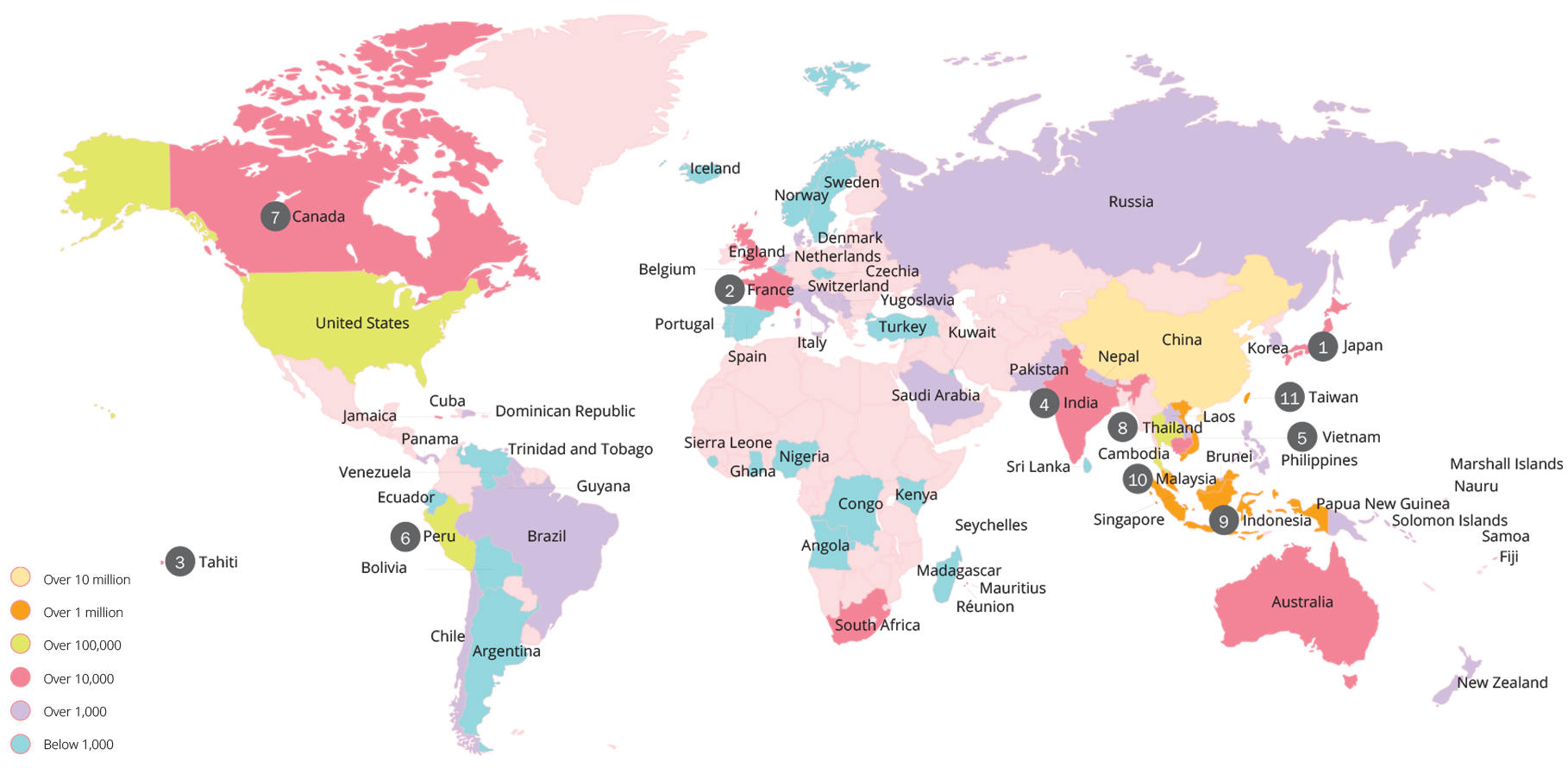

Global Hakka Population Distribution

-

❶

The Hakka community in Japan lives quietly within the fabric of society. The Chongzheng Association, operating from just a single desk, serves as the link connecting Hakka people across the country.

-

❷

Hakka have quietly blended into the rhythm of French life, yet, like other Asian communities worldwide, they still carry the label of a “model minority.”

-

❸

In the mid-20th century, faced with the strict naturalization policies of the French colonial government, the thread of Hakka ancestral records began to blur, sparking a deep desire to trace their roots.

-

❹

Kolkata is home to India’s Hakka community, who built their livelihood on the leather trade. But the Sino-Indian border war completely changed the fate of the Hakka there.

-

❺

The Hakka of Bao Long District, Bien Hoa City, Dong Nai Province, are descendants of the defeated soldiers led by General Chen Shangchuan, who followed Koxinga after his failed anti-Qing campaign in Taiwan.

-

❻

Hakka introduced the Chinese wok and stir-fry techniques, preserving Hakka cuisine in a new way while also transforming Peru’s food culture.

-

❼

After the Sino-Indian war broke out, the situation for Chinese in India became increasingly difficult. Many Hakka migrated again, bringing Indian-Hakka cuisine to Toronto, Canada.

-

❽

Hakka settled in Thailand due to 19th-century railway construction and wartime migrations. Today, under government assimilation policies and rapid modernization, the transmission of cultural heritage faces increasing challenges.

-

❾

In Banda Aceh, some Hakka converted to Islam, which meant they no longer possessed a “complete” Chinese identity—seen as a form of downward social mobility.

-

❿

In the late 20th century, Malaysia implemented the “New Economic Policy” to address poverty among the Malay population, but it deepened the Chinese community’s sense of deprivation and insecurity.

-

⓫

Taiwan has a large Hakka population, which can be divided into six subgroups by dialect: Tingzhou, Raoping, Zhao’an, Sixian, Hailu, and Dabu.

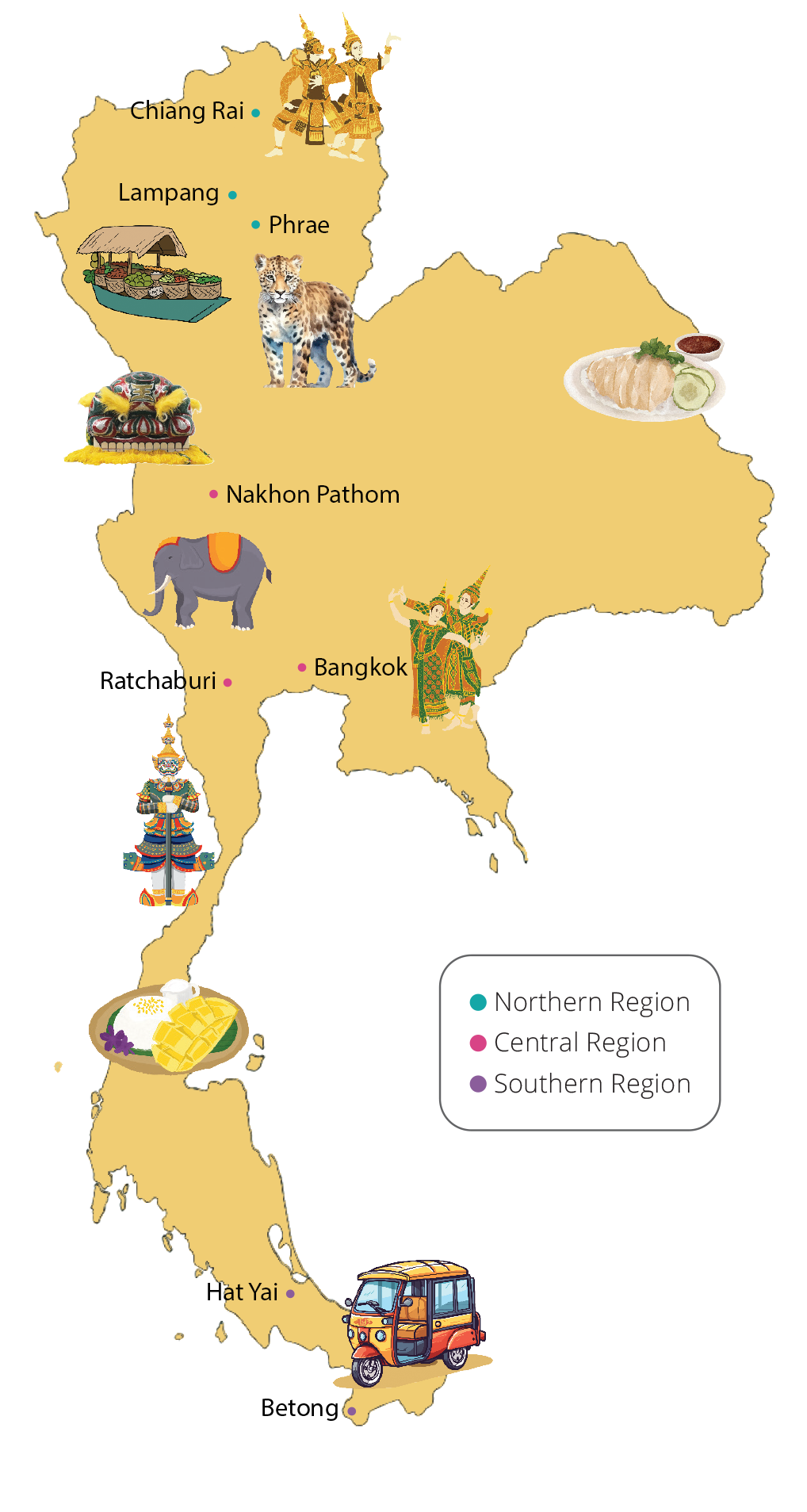

The Diversity of Hakka Communities in Thailand

Most Hakka here are “half-mountain Hakka,” originally from Fengshun in Guangdong. Because of the province’s proximity to the Chinese border, they frequently interacted with Yunnan ethnic minorities. During the Thai government’s ban on Chinese-language education, Hakka would travel to Myanmar to study Chinese education.

Lampang, the second largest city in northern Thailand after Chiang Mai, has a sizable Chinese population and a strong sense of competition among ethnic groups. This made Hakka identity especially important for the local community.

The Fengshun Hakka Association was established within the Charoen Sin School. In earlier times, Hakka associations often simultaneously founded schools, hospitals, temples, and cemeteries to meet the community’s many needs. Even today, some associations continue to run schools and remain committed to promoting Chinese-language education.

The Hakka association here still preserves many cultural artifacts of the “Hakka lion.” Unlike the traditional Chinese lion dance, the Hakka lion has a square-shaped mouth and a cuter appearance, symbolizing the Hakka people’s unity in resisting outside threats and protecting their homeland. Influenced by Teochew traditions, the Hakka in Nakhon Pathom primarily worship Pun Tao Kong (the local earth deity).

Most Hakka here are farmers or involved in the textile and timber trades. In small villages such as Huay Kra Box, ancestral worship, traditional Hakka wedding ceremonies, and funeral rites are still observed, and people in their forties and fifties still speak Hakka fluently. However, with modernization, younger generations have moved to urban areas, making the transmission of the Hakka language increasingly difficult.

Leaders of Hakka associations are mostly retired businesspeople and entrepreneurs. They travel across Thailand to give speeches, appealing to the younger generation to revitalize Hakka identity. Some have even funded the establishment of Hakka research societies, supporting Thai scholars in conducting Hakka studies.

Most Hakka here are “half-mountain Hakka.” Community pioneers such as Xie Shusi and Xu Jinrong attracted many Hakka to Hat Yai to engage in rubber planting, tin mining, and retail businesses. Today, much of Hat Yai’s commerce remains dominated by the Chinese community.

Betong is home to about 10,000 Hakka, where both the Hakka language and Chinese are well maintained. The Hakka here migrated from China to Malaysia and later moved to Thailand, where they contributed significantly to the prosperity of the local economy through rubber cultivation.

Taiwan

A Small Light, Shining Bright

Hakka mission in Taiwan is like a mustard seed: though it began small, it has grown through faith and perseverance, now shining brightly on the global map of missions.

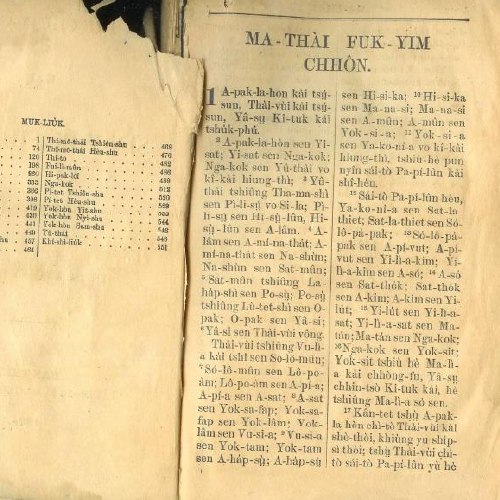

Many Hakka love to sing, and Christians are no exception. Traditional Hakka mountain songs tell of the hardships of migration, the struggles of daily life, or are sung as love duets between men and women. For Christians, singing became a way to understand the gospel. Hymns and sacred music set to Hakka melodies have also become powerful tools for evangelism in the church.

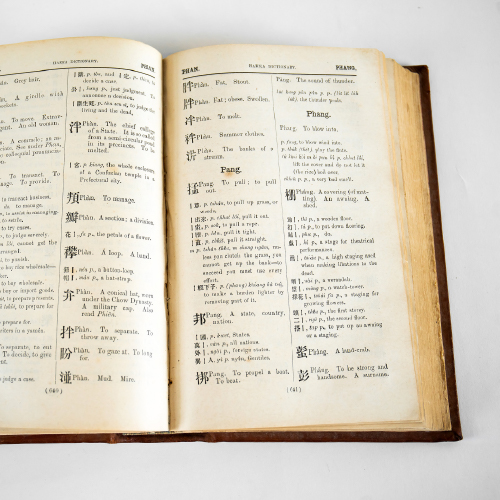

Over the past two decades, many organizations have invested deeply in Hakka-language ministry. In addition to Bible translation, another important way of helping Hakka Christians embrace the gospel while preserving their language has been through encouraging and publishing gospel music written in Hakka.

In 1999, Hakka pastors reached a consensus that Hakka mission work needed its own seminary to train pastors and missionaries. The following year, the Hakka Mission School was officially established, and in 2002 it was renamed the Christian Hakka Seminary. Seven years later, the board purchased land in Longtan, Taoyuan, and launched a fundraising campaign. In 2016, the seminary building was officially completed.

Inspired by the story of Esther, Pastor Peng De-Lang, a Hakka minister from the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, felt called to take up the responsibility of bringing the gospel to his own people. He went on to establish the Hakka Chong-Zhen Churches of Taiwan, a denomination rooted in the Hakka community. Today it has grown to 14 congregations, with 70% of its pastors fluent in Hakka and more than half of its churches composed of congregations where Hakka believers make up over 70%.

The Christian Hakka Evangelical Association (CHEA) is dedicated to publishing Hakka hymnals, promoting the Hakka Bible, linking Hakka churches in Taiwan with Hakka Christian organizations worldwide, and supporting under-resourced Hakka communities across the globe. In recent years, CHEA has also focused on raising up the younger Hakka generation by organizing youth evangelistic teams, children’s Hakka music ensembles, and short-term mission trips led by young people to serve in Hakka villages.