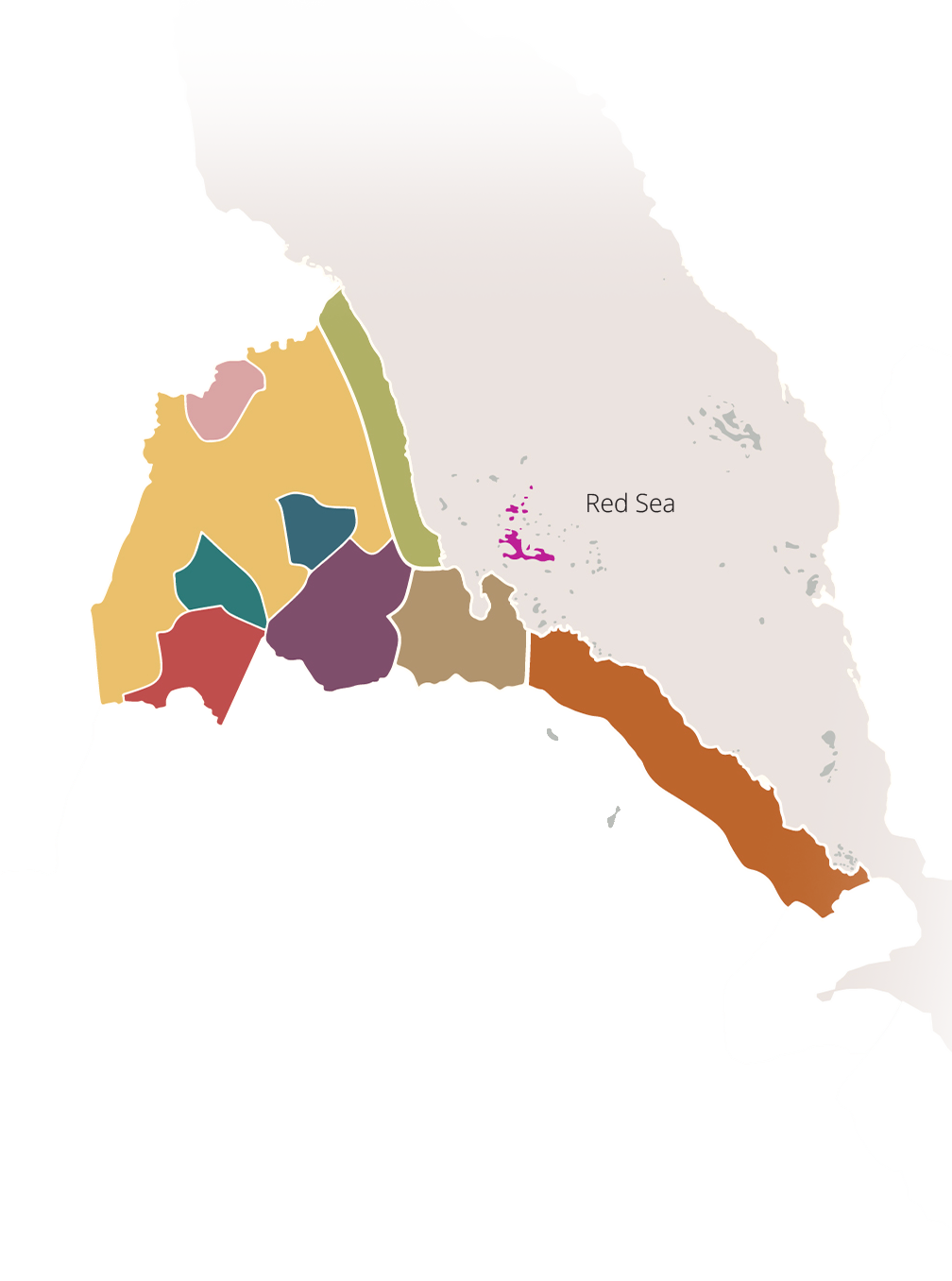

In 2024, Senegal welcomed a new president—Bassirou Diomaye Faye—who stepped onto the public stage accompanied by his two wives, instantly drawing international attention. Characterizations of the president as openly polygamous, along with portrayals of Senegal as a “man’s paradise,” quickly circulated in global media and stirred controversy.

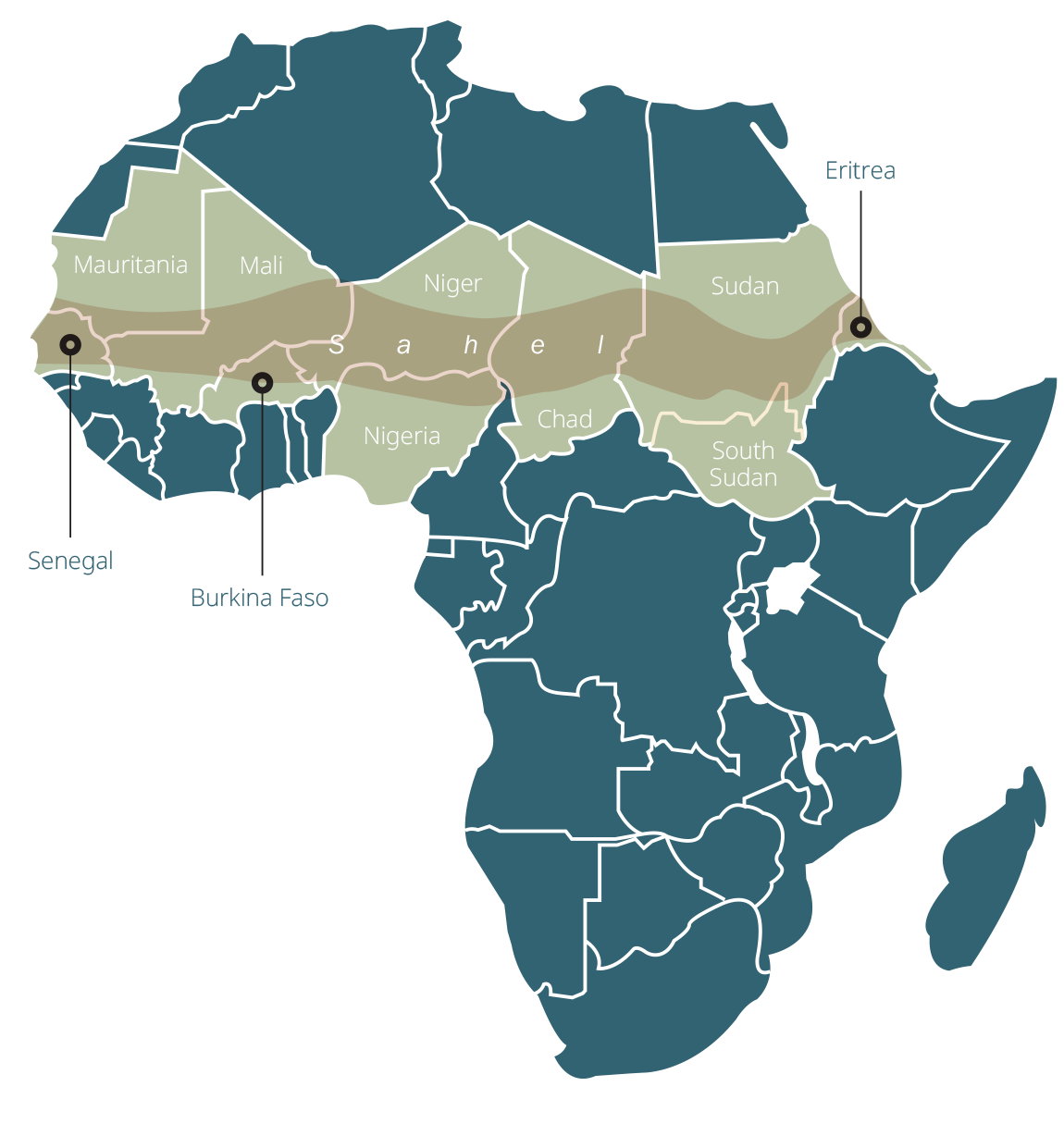

Polygamy is a long-standing tradition in West Africa. In Senegal, more than 30 percent of households still practice polygamous marriage, particularly among rural communities such as the Wolof and Fulani.

In the past, there was no limit on the number of wives a man could take. Multiple marriages expanded family influence and strengthened alliances between clans. Within traditional animist belief systems, having many wives symbolized status, power, and blessing. With the arrival of Islam in the eleventh century, marriage practices came under religious regulation. The Maliki school of Islamic law—widely followed in Senegal—teaches that a man may marry no more than four wives, and that he must treat each with fairness, both emotionally and materially.

Beyond religious and cultural factors, polygamy has also served a social function. In rural areas, women often lack the economic means to support themselves independently, and marriage provides a form of social and material security.

From the perspective of monogamous societies, polygamy may be difficult to understand. Yet in the context of mission work in West Africa, it is a lived reality that cannot be ignored—deeply intertwined with faith, tradition, and economic structures.

PRAYER

Heavenly Father, we ask that the Holy Spirit grant missionaries wisdom and discernment as they encounter the local tradition of polygamy. Help them not to judge through the lens of their own culture, but to see every soul through Your eyes, making decisions that reflect Your heart—decisions that neither weaken the power of the gospel nor neglect the wisdom of contextual mission. May they sincerely seek to understand and respect the historical, religious, social, and economic dimensions of polygamy among Senegal’s peoples. We pray that the Holy Spirit would work in human hearts, so that within their own cultural contexts, the peoples of Senegal may encounter You and experience Your love and salvation. In the name of Jesus Christ we pray, Amen.